Fundamentals of garbage collection

In the common language runtime (CLR), the garbage collector (GC) serves as an automatic memory manager. The garbage collector manages the allocation and release of memory for an application. Therefore, developers working with managed code don't have to write code to perform memory management tasks. Automatic memory management can eliminate common problems such as forgetting to free an object and causing a memory leak or attempting to access freed memory for an object that's already been freed.

This article describes the core concepts of garbage collection.

Benefits

The garbage collector provides the following benefits:

Frees developers from having to manually release memory.

Allocates objects on the managed heap efficiently.

Reclaims objects that are no longer being used, clears their memory, and keeps the memory available for future allocations. Managed objects automatically get clean content to start with, so their constructors don't have to initialize every data field.

Provides memory safety by making sure that an object can't use for itself the memory allocated for another object.

Fundamentals of memory

The following list summarizes important CLR memory concepts:

Each process has its own, separate virtual address space. All processes on the same computer share the same physical memory and the page file, if there's one.

By default, on 32-bit computers, each process has a 2-GB user-mode virtual address space.

As an application developer, you work only with virtual address space and never manipulate physical memory directly. The garbage collector allocates and frees virtual memory for you on the managed heap.

If you're writing native code, you use Windows functions to work with the virtual address space. These functions allocate and free virtual memory for you on native heaps.

Virtual memory can be in three states:

State Description Free The block of memory has no references to it and is available for allocation. Reserved The block of memory is available for your use and can't be used for any other allocation request. However, you can't store data to this memory block until it's committed. Committed The block of memory is assigned to physical storage. Virtual address space can get fragmented, which means that there are free blocks known as holes in the address space. When a virtual memory allocation is requested, the virtual memory manager has to find a single free block that is large enough to satisfy the allocation request. Even if you have 2 GB of free space, an allocation that requires 2 GB will be unsuccessful unless all of that free space is in a single address block.

You can run out of memory if there isn't enough virtual address space to reserve or physical space to commit.

The page file is used even if physical memory pressure (demand for physical memory) is low. The first time that physical memory pressure is high, the operating system must make room in physical memory to store data, and it backs up some of the data that's in physical memory to the page file. The data isn't paged until it's needed, so it's possible to encounter paging in situations where the physical memory pressure is low.

Memory allocation

When you initialize a new process, the runtime reserves a contiguous region of address space for the process. This reserved address space is called the managed heap. The managed heap maintains a pointer to the address where the next object in the heap will be allocated. Initially, this pointer is set to the managed heap's base address. All reference types are allocated on the managed heap. When an application creates the first reference type, memory is allocated for the type at the base address of the managed heap. When the application creates the next object, the runtime allocates memory for it in the address space immediately following the first object. As long as address space is available, the runtime continues to allocate space for new objects in this manner.

Allocating memory from the managed heap is faster than unmanaged memory allocation. Because the runtime allocates memory for an object by adding a value to a pointer, it's almost as fast as allocating memory from the stack. In addition, because new objects that are allocated consecutively are stored contiguously in the managed heap, an application can access the objects quickly.

Memory release

The garbage collector's optimizing engine determines the best time to perform a collection based on the allocations being made. When the garbage collector performs a collection, it releases the memory for objects that are no longer being used by the application. It determines which objects are no longer being used by examining the application's roots. An application's roots include static fields, local variables on a thread's stack, CPU registers, GC handles, and the finalize queue. Each root either refers to an object on the managed heap or is set to null. The garbage collector can ask the rest of the runtime for these roots. The garbage collector uses this list to create a graph that contains all the objects that are reachable from the roots.

Objects that aren't in the graph are unreachable from the application's roots. The garbage collector considers unreachable objects garbage and releases the memory allocated for them. During a collection, the garbage collector examines the managed heap, looking for the blocks of address space occupied by unreachable objects. As it discovers each unreachable object, it uses a memory-copying function to compact the reachable objects in memory, freeing up the blocks of address spaces allocated to unreachable objects. Once the memory for the reachable objects has been compacted, the garbage collector makes the necessary pointer corrections so that the application's roots point to the objects in their new locations. It also positions the managed heap's pointer after the last reachable object.

Memory is compacted only if a collection discovers a significant number of unreachable objects. If all the objects in the managed heap survive a collection, then there's no need for memory compaction.

To improve performance, the runtime allocates memory for large objects in a separate heap. The garbage collector automatically releases the memory for large objects. However, to avoid moving large objects in memory, this memory is usually not compacted.

Conditions for a garbage collection

Garbage collection occurs when one of the following conditions is true:

The system has low physical memory. The memory size is detected by either the low memory notification from the operating system or low memory as indicated by the host.

The memory that's used by allocated objects on the managed heap surpasses an acceptable threshold. This threshold is continuously adjusted as the process runs.

The GC.Collect method is called. In almost all cases, you don't have to call this method because the garbage collector runs continuously. This method is primarily used for unique situations and testing.

The managed heap

After the CLR initializes the garbage collector, it allocates a segment of memory to store and manage objects. This memory is called the managed heap, as opposed to a native heap in the operating system.

There's a managed heap for each managed process. All threads in the process allocate memory for objects on the same heap.

To reserve memory, the garbage collector calls the Windows VirtualAlloc function and reserves one segment of memory at a time for managed applications. The garbage collector also reserves segments as needed and releases segments back to the operating system (after clearing them of any objects) by calling the Windows VirtualFree function.

Important

The size of segments allocated by the garbage collector is implementation-specific and is subject to change at any time, including in periodic updates. Your app should never make assumptions about or depend on a particular segment size, nor should it attempt to configure the amount of memory available for segment allocations.

The fewer objects allocated on the heap, the less work the garbage collector has to do. When you allocate objects, don't use rounded-up values that exceed your needs, such as allocating an array of 32 bytes when you need only 15 bytes.

When a garbage collection is triggered, the garbage collector reclaims the memory that's occupied by dead objects. The reclaiming process compacts live objects so that they're moved together, and the dead space is removed, thereby making the heap smaller. This process ensures that objects that are allocated together stay together on the managed heap to preserve their locality.

The intrusiveness (frequency and duration) of garbage collections is the result of the volume of allocations and the amount of survived memory on the managed heap.

The heap can be considered as the accumulation of two heaps: the large object heap and the small object heap. The large object heap contains objects that are 85,000 bytes and larger, which are usually arrays. It's rare for an instance object to be extra large.

Tip

You can configure the threshold size for objects to go on the large object heap.

Generations

The GC algorithm is based on several considerations:

- It's faster to compact the memory for a portion of the managed heap than for the entire managed heap.

- Newer objects have shorter lifetimes, and older objects have longer lifetimes.

- Newer objects tend to be related to each other and accessed by the application around the same time.

Garbage collection primarily occurs with the reclamation of short-lived objects. To optimize the performance of the garbage collector, the managed heap is divided into three generations, 0, 1, and 2, so it can handle long-lived and short-lived objects separately. The garbage collector stores new objects in generation 0. Objects created early in the application's lifetime that survive collections are promoted and stored in generations 1 and 2. Because it's faster to compact a portion of the managed heap than the entire heap, this scheme allows the garbage collector to release the memory in a specific generation rather than release the memory for the entire managed heap each time it performs a collection.

Generation 0: This generation is the youngest and contains short-lived objects. An example of a short-lived object is a temporary variable. Garbage collection occurs most frequently in this generation.

Newly allocated objects form a new generation of objects and are implicitly generation 0 collections. However, if they're large objects, they go on the large object heap (LOH), which is sometimes referred to as generation 3. Generation 3 is a physical generation that's logically collected as part of generation 2.

Most objects are reclaimed for garbage collection in generation 0 and don't survive to the next generation.

If an application attempts to create a new object when generation 0 is full, the garbage collector performs a collection to free address space for the object. The garbage collector starts by examining the objects in generation 0 rather than all objects in the managed heap. A collection of generation 0 alone often reclaims enough memory to enable the application to continue creating new objects.

Generation 1: This generation contains short-lived objects and serves as a buffer between short-lived objects and long-lived objects.

After the garbage collector performs a collection of generation 0, it compacts the memory for the reachable objects and promotes them to generation 1. Because objects that survive collections tend to have longer lifetimes, it makes sense to promote them to a higher generation. The garbage collector doesn't have to reexamine the objects in generations 1 and 2 each time it performs a collection of generation 0.

If a collection of generation 0 doesn't reclaim enough memory for the application to create a new object, the garbage collector can perform a collection of generation 1 and then generation 2. Objects in generation 1 that survive collections are promoted to generation 2.

Generation 2: This generation contains long-lived objects. An example of a long-lived object is an object in a server application that contains static data that's live for the duration of the process.

Objects in generation 2 that survive a collection remain in generation 2 until they're determined to be unreachable in a future collection.

Objects on the large object heap (which is sometimes referred to as generation 3) are also collected in generation 2.

Garbage collections occur in specific generations as conditions warrant. Collecting a generation means collecting objects in that generation and all its younger generations. A generation 2 garbage collection is also known as a full garbage collection because it reclaims objects in all generations (that is, all objects in the managed heap).

Survival and promotions

Objects that aren't reclaimed in a garbage collection are known as survivors and are promoted to the next generation:

- Objects that survive a generation 0 garbage collection are promoted to generation 1.

- Objects that survive a generation 1 garbage collection are promoted to generation 2.

- Objects that survive a generation 2 garbage collection remain in generation 2.

When the garbage collector detects that the survival rate is high in a generation, it increases the threshold of allocations for that generation. The next collection gets a substantial size of reclaimed memory. The CLR continually balances two priorities: not letting an application's working set get too large by delaying garbage collection and not letting the garbage collection run too frequently.

Ephemeral generations and segments

Because objects in generations 0 and 1 are short-lived, these generations are known as the ephemeral generations.

Ephemeral generations are allocated in the memory segment that's known as the ephemeral segment. Each new segment acquired by the garbage collector becomes the new ephemeral segment and contains the objects that survived a generation 0 garbage collection. The old ephemeral segment becomes the new generation 2 segment.

The size of the ephemeral segment varies depending on whether a system is 32-bit or 64-bit and on the type of garbage collector it's running (workstation or server GC). The following table shows the default sizes of the ephemeral segment:

| Workstation/server GC | 32-bit | 64-bit |

|---|---|---|

| Workstation GC | 16 MB | 256 MB |

| Server GC | 64 MB | 4 GB |

| Server GC with > 4 logical CPUs | 32 MB | 2 GB |

| Server GC with > 8 logical CPUs | 16 MB | 1 GB |

The ephemeral segment can include generation 2 objects. Generation 2 objects can use multiple segments as many as your process requires and memory allows for.

The amount of freed memory from an ephemeral garbage collection is limited to the size of the ephemeral segment. The amount of memory that's freed is proportional to the space that was occupied by the dead objects.

What happens during a garbage collection

A garbage collection has the following phases:

A marking phase that finds and creates a list of all live objects.

A relocating phase that updates the references to the objects that will be compacted.

A compacting phase that reclaims the space occupied by the dead objects and compacts the surviving objects. The compacting phase moves objects that have survived a garbage collection towards the older end of the segment.

Because generation 2 collections can occupy multiple segments, objects that are promoted into generation 2 can be moved into an older segment. Both generation 1 and generation 2 survivors can be moved to a different segment because they're promoted to generation 2.

Ordinarily, the large object heap (LOH) isn't compacted because copying large objects imposes a performance penalty. However, in .NET Core and in .NET Framework 4.5.1 and later, you can use the GCSettings.LargeObjectHeapCompactionMode property to compact the large object heap on demand. In addition, the LOH is automatically compacted when a hard limit is set by specifying either:

- A memory limit on a container.

- The GCHeapHardLimit or GCHeapHardLimitPercent runtime configuration options.

The garbage collector uses the following information to determine whether objects are live:

Stack roots: Stack variables provided by the just-in-time (JIT) compiler and stack walker. JIT optimizations can lengthen or shorten regions of code within which stack variables are reported to the garbage collector.

Garbage collection handles: Handles that point to managed objects and that can be allocated by user code or the common language runtime.

Static data: Static objects in application domains that could be referencing other objects. Each application domain keeps track of its static objects.

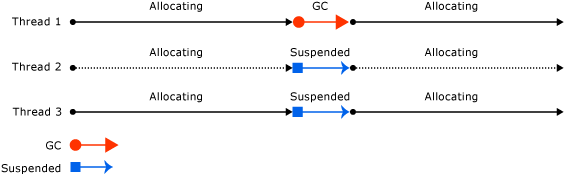

Before a garbage collection starts, all managed threads are suspended except for the thread that triggered the garbage collection.

The following illustration shows a thread that triggers a garbage collection and causes the other threads to be suspended:

Unmanaged resources

For most of the objects your application creates, you can rely on garbage collection to perform the necessary memory management tasks automatically. However, unmanaged resources require explicit cleanup. The most common type of unmanaged resource is an object that wraps an operating system resource, such as a file handle, window handle, or network connection. Although the garbage collector can track the lifetime of a managed object that encapsulates an unmanaged resource, it doesn't have specific knowledge about how to clean up the resource.

When you define an object that encapsulates an unmanaged resource, it's recommended that you provide the necessary code to clean up the unmanaged resource in a public Dispose method. By providing a Dispose method, you enable users of your object to explicitly release the resource when they're finished with the object. When you use an object that encapsulates an unmanaged resource, make sure to call Dispose as necessary.

You must also provide a way for your unmanaged resources to be released in case a consumer of your type forgets to call Dispose. You can either use a safe handle to wrap the unmanaged resource, or override the Object.Finalize() method.

For more information about cleaning up unmanaged resources, see Clean up unmanaged resources.

See also

Feedback

Coming soon: Throughout 2024 we will be phasing out GitHub Issues as the feedback mechanism for content and replacing it with a new feedback system. For more information see: https://aka.ms/ContentUserFeedback.

Submit and view feedback for